William Booth & Caistor

What he discovered in a town of just over 2,000 people, would define his life’s purpose.

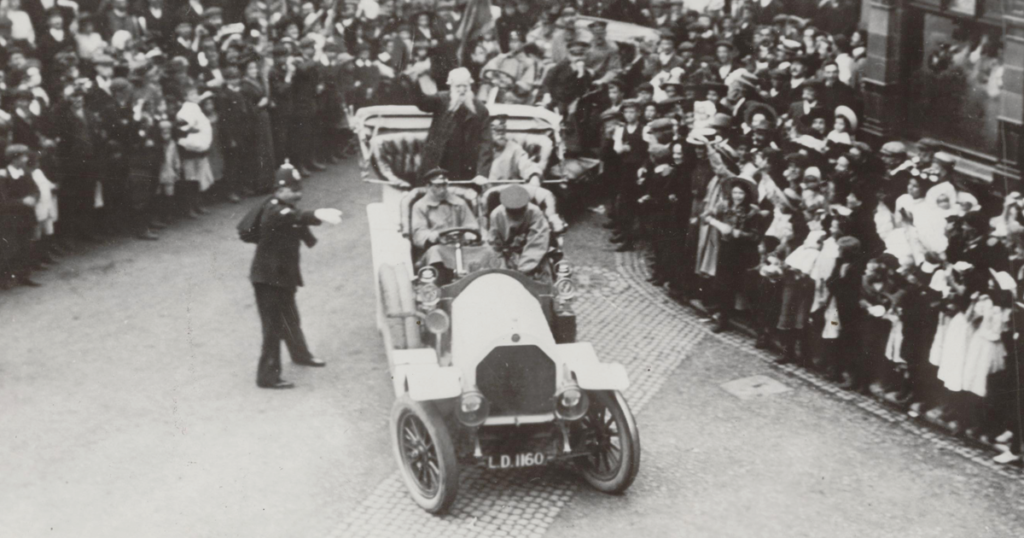

Flags, bunting and a festive air greeted General William Booth as he entered Caistor, North Lincolnshire, England on September 2, 1905. People had come by foot and by two wheeled carriages from all over the region to form a huge crowd in this small town of fewer than 2,300 souls, and a civic reception was prepared for him. For William Booth, this assemblage was not unusual—in his latter years Booth was greeted in similar fashion wherever he went.

What made this visit to Caistor different from any other was what he said there. He spoke of coming to Caistor over 50 years ago as a young man with few friends and the lasting impression it made. He said it was at Caistor that he first commenced the work that was to become so dear to him.

One Friday in December 1853, toward the end of Booth’s time as a Wesleyan Reform minister in Spalding, he received a letter from Parkin Wigelsworth, a solicitor in Donington, asking him to spend the following week in Caistor which was almost 60 miles away. Wigelsworth assured Booth that he would look after any appointments he had for that week.

Despite needing rest after recovering from illness, Booth set off the following morning after writing to his fiancée Catherine in London to tell her his plans. Earlier, he had told her how difficult it would be to leave his circuit for more than two days, even if her poor health made it necessary. Consequently, Catherine was none too pleased to hear his news, as is clear from her reply:

“I was surprised to hear of your going to Caistor, after intimating to me the impossibility of your leaving your circuit for more than two days without consequences being so serious, even if I had been so bad [ill] as to make it necessary. I am truly sorry to hear of your state of health but give up in utter despair the idea of making you judicious and prudent. After laboring in public so incessantly for a month or six weeks I cannot think it was wise to undertake to preach three times on Sunday and every night of the week. Neither do I think it was necessary or right.”

Arriving at 4 p.m., Booth discovered he was “altogether unexpected.” But rather than return, he sought out the bellman (town crier) and some friends to advertise the fact that he was there. At the meeting the following morning, Booth said, “I offered many reasons why the members should join me in seeking revival in Caistor. We knelt and gave ourselves afresh to God.” In both the afternoon and evening meetings many came under conviction and committed their lives to Christ.

In his journal, Booth highlights one case, that of a Mr. Joseph Wigelsworth, the 24-year-old brother of the man who had requested that Booth visit Caistor. Deeply troubled during the morning meeting, he returned in the afternoon and wept.

Booth spoke to him and discovered that he had been brought up in a Christian home, and despite being a Methodist for years, “he was unsaved.” As Booth spoke with him, “he broke down, came boldly to the penitent form, and with many tears and prayers he sought and obtained forgiveness. It was a splendid case and did us all good.”

The place was filled every night that followed, and 36 souls found salvation. An entry dated December 17, 1853, in the account book of Caistor’s Wesleyan Reformers reads: “To cash for Mr. Booth’s expenses £1.” Mr. Batty, the bellman, was paid one shilling for his services.

Having promised to spend another week there, Booth returned in January and was pleased to find that only two of the 36 had fallen away and returned to their previous life. With increasing congregations, the Reformers acquired a redundant congregational chapel in time for Booth’s return. The result was “a glorious harvest.” Booth recorded that 76 were saved that week.

But there were critics. The Reformers, to which Booth belonged, had only commenced their services in Caistor a few weeks before Booth’s first visit, but had grown significantly. There were already 35 members when he first arrived, 80 by Christmas and over 200 by the end of his third visit in February. One newspaper correspondent spoke of them as having “hewn, partly out of the rough and partly from other sects, Ranters, Independents and Nothingarians, a sect of their own.” He stated that, in the “‘revival meetings’ as they are technically called…the wildest fanaticism is encouraged; ravings and bawling, and all manner of extravagant doings are permitted.”

At the end of his final visit in the February of 1854, shortly before he moved to London, Booth wrote, “Every night many souls saved… The parting with this dear people was very painful. I had never experienced anything approaching to the success with which God crowned my labors here.” Booth loved Caistor. He returned in June and again the following year with his new bride.

On his visit in 1905, the chairman of the council spoke of the “abiding results” of Booth’s “unwearied self-denying labors as an Evangelist in this town 50 years ago.” In Caistor God showed Booth how to reach the lost beyond the chapel confines. With all that he achieved in founding The Salvation Army, soul-saving would ever remain what he called his “life’s business.”

This article was originally published in the January 2016 issue of The War Cry. Photo via The Salvation Army National Archives.